Food Safety With Temperature

This post is a deep-dive on how to prevent food spoilage and foodborne illness using temperature.

It’s part of my broader framework on food safety, which aims to be clearer and more actionable for home cooks than existing food safety guidelines.

WHAT’S THE POINT?

Harmful bacteria, parasites, mold, and viruses might be in your food. To reduce the chances of food spoilage and foodborne illness caused by these pathogens, you need to both:

Kill any existing pathogens in your food. These pose the most immediate risks. You should kill them (or reduce them to safe levels) where possible.

Prevent any new pathogens from growing in your food. If you haven’t totally killed the existing pathogens in your food (or if your food is exposed to other pathogens after the fact), the few that remain will multiply over time. This is especially important for foods that you aren’t eating right away (e.g. food you are storing or cooking over multiple hours)

Proper temperature control can achieve both of these goals. This guide will start with a few simple rules then dive into details (so you know when it is safe to break the rules!).

THE CHEAT SHEET

To kill existing pathogens

To kill any existing pathogens in your food, you need to heat your food to temperatures that kill those pathogens. Since each food has a unique risk level when it comes to existing pathogens, the temperature you heat your food to depends on the food you’re cooking. Here are a few handy pasteurization temperatures:

Beef, lamb, and pork: 158ºF or 145ºF held for 4 minutes or 140ºF held for 12 minutes or 130ºF held for 112 minutes

Chicken, turkey and duck: 165ºF or 140ºF held for 30 minutes or 130ºF for 6 hours

Fish: 145º or the thickness-specific guidelines here

Shellfish: 194°F (90°C) for 90 seconds

As you can see, holding foods at specific temperatures for long periods of time enables you to cook food to lower temps (for juicier meat!). Doing so usually requires a sous vide device, but your chicken will thank you!

Since the temperature to pasteurize fish and shellfish generally ruins the taste of those foods, it’s more common to buy fish that is fresh (or that was frozen while it was fresh) and skip the pasteurization step.

To prevent new pathogens from growing

To prevent any new pathogens from growing in your food, you need to keep your food at temperatures where pathogens fail to grow. As a rule of thumb, new harmful microorganisms can only grow between 40ºf and 140ºf. That’s why we call that range the temperature danger zone.

If your food must be in the temperature danger zone, it should be there for less than 2 hours total (including the time to warm up or cool down your food). If you’re eating it right away, 4 hours is fine.

THE DEtails

To Kill Existing Pathogens

You can kill most harmful pathogens with high temperatures. There are two ways to do it:

With high temperature: Each pathogen has a temperature at which it will immediately die. For example, Salmonella will die when exposed to temperatures exceeding 165ºf. That’s why we were traditionally told to cook a chicken to 165ºf. Norovirus will die when exposed to temperatures exceeding 145ºf. Clostridium botulinum (the bacteria that causes botulism) will die when exposed to temperatures exceeding 250ºf. This is why low acid shelf-stable foods are canned under extreme heat.

With not as high a temperature but more time: If you can hold food at a consistent temperature, you can rely on temperature and time to kill microorganisms at a lower overall temp. For example, salmonella will die when brought to 140ºf and then kept at that temperature for 30 minutes (or at 130ºf for 6 hours). That’s why we can cook chicken sous vide at lower temperatures than 165ºf provided we cook it for long enough. Here’s an extremely detailed guide if you want to learn more about this time/temp relationship for different foods.

Low temperatures aren’t a great way to kill existing microorganisms and viruses, because some of the worst bacteria (such as the ones that cause botulism) and norovirus can survive at extremely low temperatures.

Varying temperature requirements due to risk levels

Different foods require different temperatures to pasteurize because foods have varying risk levels when it comes to their existing pathogens.

Chicken, for example, is highly susceptible to salmonella while beef and fish (and even duck) are not. This is in part because beef and fish generally come from whole-muscle cuts and so are less exposed to surface contamination (and so even beef tartare is pretty safe). Ground beef, meanwhile, is not a whole-muscle cut, and so surface-level pathogens are distributed throughout the meat. Chicken is also more susceptible to salmonella because it is generally raised in nastier conditions than beef, fish, and duck.

These risk levels can change over time. Decades ago, the bacteria trichinella was common in pork, so food guidelines for pork were particularly stringent (and our parents cooked our pork white!). Today, thanks to better farming, the bacteria is less common and our understanding of trichinella is deeper. The US government recommends holding pork at 15 minutes at 132°F (55.6°C) or for 1 minute at 140°F (60°C).

Similarly, different parts of the world (or even individual food vendors) have varying levels of pathogen risk. Japan is known for a chicken farming industry with lower instances of salmonella (but is certainly not without risk).

To kill parasites in raw fish

Industrial flash freezer

Parasites (such as those found in raw fish) can also survive at low temperatures, but they do die after enough time below freezing. Specifically, these parasites die after either 7 days at -4ºf or 15 hours at -31ºf. Your freezer likely doesn’t go that low.

In many jurisdictions (even some home to 3 Michelin star sushi restaurants), it is illegal to serve raw fish without freezing it first. Industrial flash-freezers are used by the restaurant industry to freeze fish at extremely fast speeds to maintain quality. Don’t take this to mean that frozen fish are necessarily safe, as they are still susceptible to bacteria infections.

Different fish have different parasite risks based on their build and dietary habits. That’s why shellfish, certain species of tuna, and certain types of farm-raised fish are often exempt in jurisdictions where freezing raw seafood is otherwise required. In general, freshwater fish are of higher risk than saltwater fish.

To prevent new pathogens from growing

If you haven't completely killed all existing pathogens in your food, or if your food might be contaminated from outside sources, you also need to worry about the growth of new pathogens.

You can prevent the pathogens in your food from multiplying with either really high or really low temperatures. As a rule of thumb, new harmful microorganisms can only grow between 40ºf and 140ºf. That’s why we call that range the temperature danger zone.

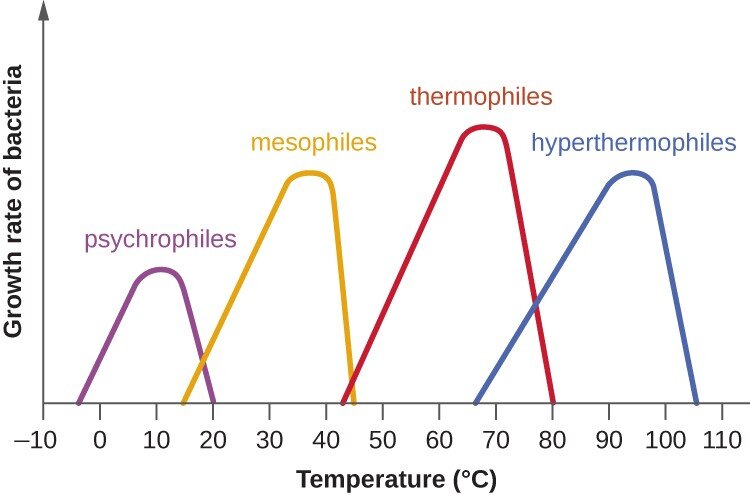

Each bacteria has an ideal temperature for growth.

Food that is not otherwise preserved should stay out of the temperature danger zone (either warmer or colder). If your food must be in the temperature danger zone, it should be there for less than 2 hours total (including the time to warm up or cool down your food).

That means you can pretty much keep food above 140ºf indefinitely without new harmful microorganisms growing. It also means you should keep perishable foods below 40ºf, though some common microorganisms can still survive this.

Pyschrophiles (which is greek for ‘cold loving’) can survive up to -4ºf, and they are often why your food spoils over time even when it is in the fridge. They tend to be less dangerous than the bacteria that grow at warmer temperatures.

Deviating from the temperature danger zone

The stated temperature danger zone includes a margin of error. In California, for example, food safety guidelines deem the temperature danger zone from 41ºf to 135ºf. In Australian regulations, foods can be kept below 140ºf for 4 hours (rather than 2) provided they are used or served immediately.

The differences lie in risk tolerance. The actual temperature where harmful bacteria fail to grow is closer to 126.1ºf, but this temperature is dangerously close to the temperatures where bacteria grow most rapidly. Without a highly calibrated and consistent heating device, keeping your food at that low a temperature is dangerous. For this reason, you’ll often see recommendations where food can be kept at 130ºf if cooked sous vide (on a calibrated device) but 140º otherwise.

Implications of the temperature danger zone

Cooking isn’t the only time you need to worry about the temperature danger zone. You also need to worry about it when you are putting away finished food.

If you put a big container of hot broth in the fridge, it will likely stay in the temperature danger zone for too long as it reaches fridge temps. When cooling down food for the refrigerator, do so rapidly (e.g. with an ice water bath or an ice wand).

Similarly, once you’ve cooked away the pathogens in your food, be sure not to place it on the same plate or cutting board where you had food that was raw.

ways to break the rules

Temperature is the best way to kill existing bacteria. But there are other ways to prevent new bacteria from forming (so you can ignore the temperature danger zone):

Decrease the pH to 4.6 or lower. High acid foods are protected from new bacteria growth.

Decrease the water activity level to 0.85 or lower. Low water activity foods are protected from new bacteria growth.

You can learn more about the other types of food preservation methods here.

FAQS

Is eating beef tartare safe? Usually. The most common pathogens in beef are surface-level. When beef tartare is prepared, it is prepared from whole-muscle cuts that are not exposed to these surface-level pathogens. As such, provided the beef is fresh, the primary risks are from contaminated work surfaces or utensils (so similar to the risks of eating raw vegetables).

Is eating rare steak safe? Usually. The most common pathogens in beef are surface-level. Steak is typically prepared from whole-muscle cuts that are not exposed to these surface-level pathogens. Further, the sear typically kills any surface-level contamination. As such, the primary risks are from contaminated utensils after the steak is seared.

Is it safe to eat frozen fish from the grocery store raw? Probably not. While freezing fish at low temperatures can kill parasites, frozen fish from the grocery store might still have bacteria. These fish are not typically prepared for raw consumption, so they might have even been unfrozen and frozen again, increasing the chances of bacterial infection. I don’t take the risk.

Is eating rare or medium-rare duck safe? Usually. While ducks are at risk of salmonella like chicken, the risk is lower because ducks are raised in different conditions than chicken.

Which fish are safe to eat raw? There is no way to eliminate risk entirely, but you can take steps to reduce both parasite and bacteria risk. Here's what I do when buying fish for raw preparation:

Choose a fish with no or low risk of parasites. These are either shellfish, types of tuna, or fish that have been frozen specifically for this purpose. I am personally willing to take the parasite risk with mackerel, sea bass, farmed rainbow trout, halibut, turbot, and snapper. I do not buy freshwater fish as the chances of parasites are high. I also do a visual inspection for parasites (they look like little worms).

Eliminate the chance of bacterial infection. This requires buying fish that is fresh (or that was frozen fresh), keeping the fish out of the temperature danger zone, and keeping your work station clean. I buy whole fish (rather than filets, except with tuna) and I eat my fish the day I buy it.

Is eating raw shrimp safe? Usually not. While the risks are similar to those of raw oysters, the risk level is higher with most store-bought shrimp because they are not stored as meticulously as oysters. In fact, they are often frozen and unfrozen and frozen again! I eat raw shrimp at gourmet restaurants (who are in direct contact with meticulous fishers and distributors) but otherwise prefer boiling my shrimp and chilling it before serving it “raw”.